The Unyielding Soil: How Hell or High Water Paved the Way for Yellowstone’s Modern Western Legacy

Before Taylor Sheridan became a household name synonymous with sprawling neo-Western dramas like Yellowstone, he meticulously carved out a distinguished writing career through a series of critically acclaimed films. While his work on intense thrillers like Sicario demonstrated a versatile talent stretching beyond the confines of the American West, it was a particular cinematic masterpiece that truly showcased his unique vision for revitalizing the genre, laying the thematic groundwork for his later television triumphs. This film, an underrated gem that fans of Yellowstone absolutely need to discover, powerfully articulates the modern perspectives Sheridan brings to the Western while simultaneously delivering the rugged thrills and compelling character studies that genre enthusiasts crave.

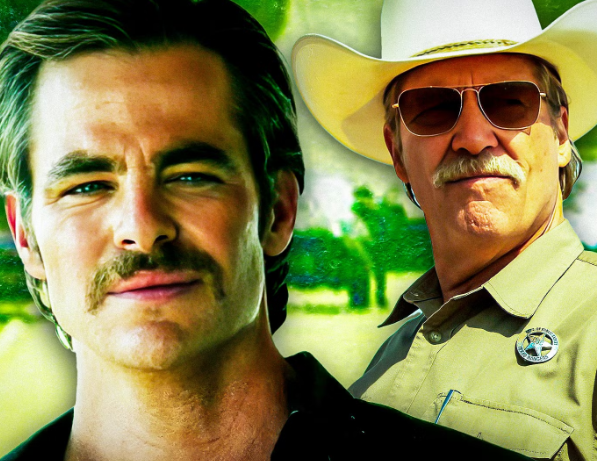

That film is 2016’s Hell or High Water. A terrific crime drama, it expertly blends elements of a heist story with the profound emotional resonance and moral complexities of a modern Western. Written by Taylor Sheridan and directed by David Mackenzie, the movie stars Chris Pine and Ben Foster as Toby and Tanner Howard, two brothers who embark on a desperate bank-robbing spree across West Texas. Their illicit activities attract the attention of a relentless, aging Texas Ranger named Marcus Hamilton, played with weary brilliance by Jeff Bridges. At its core, Hell or High Water is a stark examination of economic desperation, the decay of rural America, and the lengths individuals will go to protect their legacy in a system stacked against them.

The genius of Hell or High Water lies in its masterful use of classic Western tropes to dissect the realities of modern America. The Howard brothers, much like the legendary outlaws of the Old West, are portrayed as complex, flawed protagonists. Their mission isn’t driven by malice or pure greed, but by a visceral need to save their family ranch from foreclosure by the very banks they are robbing. This fundamental premise instantly elevates them to a kind of folk hero status, a desperate pair fighting back against an indifferent corporate entity that embodies the contemporary antagonist. Toby, the quieter and more contemplative brother, is deeply motivated by the desire to secure a future for his estranged children, ensuring they inherit the land that has been in their family for generations. Tanner, the volatile and impulsive ex-con, is driven by a chaotic blend of loyalty to his brother and an unbridled thirst for the thrill, often pushing their enterprise into darker, more violent territory. Their journey through a landscape dotted with ghost towns, poverty-stricken communities, and the looming shadows of oil pumpjacks perfectly illustrates a modern frontier, where the battle isn’t for gold or cattle, but for basic survival and the retention of one’s heritage.

The thematic resonance between Hell or High Water and Yellowstone is undeniable, almost as if the film served as a concentrated blueprint for the expansive television series. Yellowstone became one of the most popular shows on television, catapulting Sheridan’s career to new heights, and while he has since crafted an entire universe of compelling dramas, Hell or High Water remains a crucial piece for understanding his overarching vision. Both narratives, despite their vastly different plot structures – one a tightly wound heist thriller, the other a sprawling family saga – share a profound preoccupation with the fight to hold onto ancestral land and a traditional way of life against the relentless march of modernity and corporate expansion.

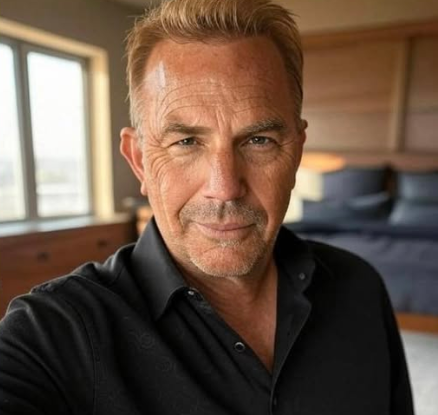

At the very heart of both stories is the unyielding resolve of a patriarch to preserve his family’s inheritance for future generations. In Hell or High Water, it is Toby Howard’s desperate gamble to save his children from the cycle of poverty and landlessness. In Yellowstone, this fight is personified by Kevin Costner’s John Dutton, a rancher whose entire identity, and indeed his family’s, is intrinsically tied to the sprawling Yellowstone Dutton Ranch. John Dutton’s mission is not merely about owning land; it’s about safeguarding a legacy, a culture, and a way of life that he believes is sacred and under siege from all sides – land developers, environmentalists, the federal government, and the encroaching forces of tourism and urbanization. The lengths to which both Toby and John go, and the moral ambiguities they navigate, underscore Sheridan’s understanding that in the modern Western, the lines between good and bad are rarely straightforward.

Sheridan consistently portrays characters forced to operate in grey areas, often resorting to extralegal or morally questionable means to protect what they deem invaluable. The Howard brothers commit felonies, yet audiences are compelled to empathize with their plight. Similarly, John Dutton and his family frequently cross ethical boundaries, employ intimidation, political maneuvering, and even violence to secure the ranch’s future. The famous line “We’re criminals, John. But we’re good men,” delivered by Rip Wheeler, could just as easily apply to the morally complex protagonists of Hell or High Water. This nuanced portrayal of heroism and villainy, where desperation often dictates morality, is a hallmark of Sheridan’s storytelling.

The theme of generational legacy and the burden of inheritance is another strong through-line. Sheridan himself makes a brief but memorable cameo in Hell or High Water as a cowboy, leading his cattle away from a wildfire threatening his land. His lament, “And I wonder why my kids won’t do this s for a living,” perfectly encapsulates the struggle of passing down a demanding, often thankless, way of life. This sentiment echoes throughout Yellowstone, as John Dutton grapples with his children’s complex relationships with the ranch – Beth’s fierce loyalty mixed with her own demons, Kayce’s desire for a simpler life away from the ranch’s politics, and Jamie’s tormented struggle between his Dutton identity and his own ambitions. The weight of the ranch’s legacy often feels more like a curse than a blessing to the Dutton offspring, yet John remains steadfast in his mission to ensure its continuity.

Moreover, the cast itself provides a direct link between the two works. Gil Birmingham, who delivers a powerful performance as Ranger Alberto Parker in Hell or High Water, transitions seamlessly into the pivotal role of Thomas Rainwater in Yellowstone. Rainwater, the astute and determined chief of the Broken Rock Indian Reservation, wages his own battle for ancestral land, seeking to reclaim what was taken from his people. His struggle adds another compelling layer to the “land ownership” theme, challenging the Duttons’ claims and highlighting the complex, often tragic, history of the American West. Birmingham’s presence in both works reinforces the idea that Sheridan is exploring a consistent set of ideas and conflicts across his narrative universe.

In conclusion, Hell or High Water is far more than just an excellent standalone film; it is a foundational text in Taylor Sheridan’s oeuvre, a powerful precursor that illuminates the core themes and narrative strategies he would later expand upon in Yellowstone. Both narratives dissect the pressures of a fading way of life, the economic injustices faced by rural communities, and the often morally compromised choices made in the name of family and legacy. By understanding the desperation of Toby Howard’s fight for his children’s future, one gains a deeper appreciation for the relentless, often brutal, commitment of John Dutton to his sprawling ranch. Hell or High Water is an essential viewing experience for any fan of Yellowstone, offering a concise, raw, and equally compelling exploration of the unyielding soil that defines Taylor Sheridan’s modern Western vision.